2021 ACR/VF Guideline for ANCA-associated Vasculitis (GPA/MPA/EGPA)

This guideline presents the first recommendations endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology and the Vasculitis Foundation for the management of AAV and provides guidance to health care professionals on how to treat these diseases.

After these guidelines were written, the medication avacopan (Tavneos ®) was approved by the FDA as an adjunctive treatment in adults for severe active ANCA-associated vasculitis (specifically MPA and GPA) in combination with standard therapy including glucocorticoids. Avacopan (Tavneos®) may help to reduce exposure to glucocorticoids.

Plain Language Recommendations

The ACR/VF Clinical Practice Guidelines were written for medical practicioners to help guide them in their treatment of patients with vasculitis. The plain language versions of these guidelines focus on the information that is most important for the majority of patients to know, and are written in language that can be easily understood by those who do not have a medical background.

MPA & GPA Plain Language

- All Treatment Recommendations For MPA & GPA

- GPA/MPA Treatment Recommendations

- GPA/MPA Medication Recommendations

- GPA/MPA Recommendations for Specific Symptoms

- GPA/MPA Recommendations for Related Conditions

EGPA Plain Language

- All Treatment Recommendations For EGPA

- Treatment Recommendations for Severe EGPA

- Treament Recommendations for Nonsevere EGPA

- General EGPA Recommendations

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xricdR8Esgchttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xricdR8Esgc

General Information

Sharon A. Chung,1 Carol A. Langford,2 Mehrdad Maz,3![]() Andy Abril,4 Mark Gorelik,5 Gordon Guyatt,6 Amy M. Archer,7 Doyt L. Conn,8

Andy Abril,4 Mark Gorelik,5 Gordon Guyatt,6 Amy M. Archer,7 Doyt L. Conn,8![]() Kathy A. Full,9 Peter C. Grayson,10

Kathy A. Full,9 Peter C. Grayson,10![]() Maria F. Ibarra,11 Lisa F. Imundo,5 Susan Kim,1 Peter A. Merkel,12

Maria F. Ibarra,11 Lisa F. Imundo,5 Susan Kim,1 Peter A. Merkel,12![]() Rennie L. Rhee,12

Rennie L. Rhee,12![]() Philip Seo,13 John H. Stone,14

Philip Seo,13 John H. Stone,14![]() Sangeeta Sule,15

Sangeeta Sule,15![]() Robert P. Sundel,16 Omar I. Vitobaldi,17 Ann Warner,18 Kevin Byram,19 Anisha B. Dua,7 Nedaa Husainat,20

Robert P. Sundel,16 Omar I. Vitobaldi,17 Ann Warner,18 Kevin Byram,19 Anisha B. Dua,7 Nedaa Husainat,20![]() Karen E. James,21 Mohamad A. Kalot,22

Karen E. James,21 Mohamad A. Kalot,22![]() Yih Chang Lin,23 Jason M. Springer,3

Yih Chang Lin,23 Jason M. Springer,3![]() Marat Turgunbaev,24 Alexandra Villa-Forte,2 Amy S. Turner,24

Marat Turgunbaev,24 Alexandra Villa-Forte,2 Amy S. Turner,24 and Reem A. Mustafa25

and Reem A. Mustafa25![]()

Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient. The ACR considers adherence to the recommendations within this guideline to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding their application to be made by the physician in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are intended to promote beneficial or desirable outcomes but cannot guarantee any specific outcome. Guidelines and recommendations developed and endorsed by the ACR are subject to periodic revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice. ACR recommendations are not intended to dictate payment or insurance decisions, and drug formularies or other third-party analyses that cite ACR guidelines should state this. These recommendations cannot adequately convey all uncertainties and nuances of patient care.

The American College of Rheumatology is an independent, professional, medical and scientific society that does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse any commercial product or service.

Objective. To provide evidence-based recommendations and expert guidance for the management of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody– associated vasculitis (AAV), including granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

Methods. Clinical questions regarding the treatment and management of AAV were developed in the population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO) format (47 for GPA/MPA, 34 for EGPA). Systematic literature reviews were conducted for each PICO question. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation methodology was used to assess the quality of evidence and formulate recommendations. Each recommendation required ≥70% consensus among the Voting Panel.

Results. We present 26 recommendations and 5 ungraded position statements for GPA/MPA, and 15 recommendations and 5 ungraded position statements for EGPA. This guideline provides recommendations for remission induction and maintenance therapy as well as adjunctive treatment strategies in GPA, MPA, and EGPA. These recommendations include the use of rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in severe GPA and MPA and the use of mepolizumab in nonsevere EGPA. All recommendations are conditional due in part to the lack of multiple randomized controlled trials and/or low- quality evidence supporting the recommendations.

Conclusion. This guideline presents the first recommendations endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology and the Vasculitis Foundation for the management of AAV and provides guidance to health care professionals on how to treat these diseases.

The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV) comprise granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, Churg-Strauss). These diseases affect small- and medium-sized vessels and are characterized by multisystem organ involvement.

GPA is characterized histologically by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in addition to vasculitis. Common clinical manifestations include destructive sinonasal lesions, pulmonary nodules, and pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. GPA is most commonly associated with cytoplasmic ANCA and antibodies to proteinase 3 (PR3). Among European populations, prevalence ranges from 24 to 157 per million, with the highest prevalence reported in Sweden and the UK.[1]

MPA is characterized histologically by vasculitis without granulomatous inflammation. Common clinical manifestations include rapidly progressive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis and alveolar hemorrhage. MPA is most commonly associated with perinuclear ANCA and antibodies to myeloperoxidase. The prevalence of MPA ranges from 0 to 66 cases per million among European countries and 86 cases per million in Japan.[1, 2]

EGPA is characterized histologically by eosinophilic tissue infiltration in addition to vasculitis. Common clinical manifestations include asthma, peripheral eosinophilia, and peripheral neuropathy. Only 40% of patients produce detectable ANCA. The overall prevalence of EGPA in European populations has been estimated to range from 2 to 38 cases per million.[1, 3]

Prior to the use of alkylating agents, survival with these diseases was quite poor (e.g., median survival of patients with GPA was ~5 months).[4] Current treatment regimens have reversed this poor prognosis, but treatments are still associated with toxicity. Recent clinical trials have investigated the efficacy and toxicity of both biologic and nonbiologic immunosuppressive agents for the treatment of AAV. Observational studies have provided additional insight regarding management strategies for these diseases. Therefore, this guideline was developed to provide evidence-based recommendations for the treatment and management of GPA, MPA, and EGPA. Although this guideline may inform an international audience, these recommendations were developed considering the experience and availability of treatment and diagnostic options in the US.

This guideline followed the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline development process (https://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Clinical-Practice- Guidelines) using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to rate the quality of evidence and develop recommendations (5,6). ACR policy guided the management of conflicts of interest and disclosures (https://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/ Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Vasculitis). Supplementary Appendix 1 (available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at

http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41773/abstract) presents a detailed description of the methods. Briefly, the Literature Review team undertook systematic literature reviews for predetermined questions addressing specific clinical populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes (PICO). An in-person Patient Panel of 11 individuals with different types of vasculitis (4 patients with GPA, 1 patient with MPA, and 2 patients with EGPA) was moderated by a member of the Literature Review team (ABD). This Patient Panel reviewed the evidence report (along with a summary and interpretation by the moderator) and provided patient perspectives and preferences. The Voting Panel comprised 9 adult rheumatologists, 5 pediatric rheumatologists, and 2 patients; they reviewed the Literature Review team’s evidence summaries and, bearing in mind the Patient Panel’s deliberations, formulated and voted on recommendations.

The Voting Panel was assembled for the ACR and Vasculitis Foundation’s broad effort to develop recommendations for 7 forms of systemic vasculitis: giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki syndrome, and the 3 AAVs presented in this report. The physicians on this panel included rheumatologists who could provide insight on all of these diseases and did not include other subspecialists who would not have experience with many of the other vasculitides addressed in this effort (e.g., pulmonologists who would not have experience with large- or medium-sized vessel vasculitis). The Literature Review team chair was a nephrologist. The patients on the Voting Panel presented the views of the Patient Panel, which consisted of patients with different types of vasculitis. A recommendation required ≥70% consensus among the Voting Panel.

How to interpret the recommendations

A strong recommendation is usually supported by moderate- to high-quality evidence (e.g., multiple randomized controlled trials). For a strong recommendation, the recommended course of action would apply to all or almost all patients. Only a small proportion of clinicians/patients would not want to follow the recommendation. In rare instances, a strong recommendation may be based on very low– to low-certainty evidence. For example, an intervention may be strongly recommended if it is considered benign, low-cost, without harms, and the consequence of not performing the intervention may be catastrophic. An intervention may be strongly recommended against if there is high certainty that the intervention leads to more harm than the comparison with very low or low certainty about its benefit (7).

In this guideline, we present the first ACR/Vasculitis Foundation recommendations for the management of GPA, MPA, and EGPA. Although these recommendations provide a general guide for disease management, the patient’s clinical condition, preferences, and values should influence their treatment. Overall, these recommendations reflect the evolving management of these diseases, including the new roles for biologic therapies and aggressive strategies to minimize glucocorticoid toxicity. The recommendations for GPA and MPA are supported by a greater number of randomized trials than are currently available in EGPA. All of the recommendations made for these 3 diseases are conditional, which indicates that there are settings in which the evidence is not strong or an alternative is a reasonable consideration. These recommendations should not be used by any agency to restrict access to therapy or require that certain therapies be utilized prior to other therapies.

The physicians on the Voting Panel were primarily rheumatologists, because the recommendations were being developed for rheumatologists in the US. Since AAVs are multisystem diseases, patients with AAVs often receive care from other medical subspecialists (e.g., nephrologists, pulmonologists, and/or otolaryngologists). While the recommendations presented in this guideline are driven by the published data, other medical subspecialists may favor a different management strategy. We encourage rheumatologists to discuss treatment plans and coordinate care with other subspecialists as needed.

Recently, a clinical trial of avacopan in patients with GPA and MPA was published (55). This guideline development effort did not include consideration of avacopan, since the guidelines consider therapies that are approved by the FDA for use for any indication at the time of the last literature search. Therapies approved by the FDA after that date will be considered for inclusion in future updates to this guideline.

This guideline highlights gaps in our knowledge for the treatment of AAV. Most glaring is the lack of biomarker assessments or other noninvasive diagnostic testing with minimal toxicity that can accurately assess disease activity and predict outcomes. In addition, while we have evidence from randomized clinical trials to support recommendations regarding initial remission induction and maintenance therapy, critical questions remain unanswered, such as the optimal duration of therapy.

These gaps in knowledge reinforce the need for ongoing research in these diseases. Specific areas to investigate include the following:

1) biomarker studies to identify more specific, reliable indicators of disease activity that can guide treatment decisions;

2) trials to clarify how best to use the currently available medications (e.g., dosing, duration, effective combinations, and in which population to use which drugs);

3) trials to identify novel, targeted, and/or glucocorticoid- sparing agents with minimal toxicity; and

4) long- term studies to understand the course of disease and the safety of current therapies.

We hope significant progress will be made in these areas such that future recommendations provide a more tailored approach to disease management, minimize treatment toxicity, and prevent organ damage in these patients.

We thank Anne M. Ferris, MBBS, Ora Gewurz- Singer, MD, Rula Hajj-Ali, MD, Eric Matteson, MD, MPH, Robert F. Spiera, MD, Linda Wagner- Weiner, MD, MS, and Kenneth J. Warrington, MD, for serving on the Expert Panel. We thank Antoine G. Sreih, MD, and Gary S. Hoffman, MD, MS, for their contributions during the early phases of this project as members of the Core Team. Dr. Hoffman’s participation ended July 2018 due to personal reasons. Dr. Sreih’s involvement ended in December 2018 when he became primarily employed by industry, which precluded his continued participation in this project. We thank Joyce Kullman (Vasculitis Foundation) for her assistance with recruitment for the Patient Panel. We thank the patients who (along with authors Kathy A. Full and Omar I. Vitobaldi) participated in the Patient Panel meeting: Jane Ascroft, Scott A. Brunton, Dedra DeMarco, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jenn Gordon, Maria S. Mckay, Sandra Nye, Stephanie Sakson, and Ben Wilson. We thank Robin Arnold, Catherine E. Najem, MD, MSCE, and Amit Aakash Shah, MD, MPH, for their assistance with the literature review. We thank the ACR staff, including Ms Regina Parker, for assistance in organizing the face- to- face meeting and coordinating the administrative aspects of the project, and Ms Robin Lane for assistance in manuscript preparation. We thank Ms Janet Waters for help in developing the literature search strategy and performing the initial literature search, and Ms Janet Joyce for performing the update searches.

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Drs. Chung and Langford had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Chung, Langford, Maz, Abril, Gorelik, Guyatt, Archer, Full, Grayson, Merkel, Seo, Stone, Sule, Sundel, Vitobaldi, Turner, Mustafa.

Acquisition of data. Chung, Langford, Maz, Abril, Gorelik, Full, Imundo, Kim, Merkel, Stone, Vitobaldi, Byram, Dua, Husainat, James, Kalot, Lin, Springer, Turgunbaev, Villa- Forte, Turner, Mustafa.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Chung, Langford, Maz, Abril, Gorelik, Archer, Conn, Full, Grayson, Ibarra, Imundo, Kim, Merkel, Rhee, Seo, Stone, Vitobaldi, Warner, Byram, Dua, Husainat, Kalot, Lin, Springer, Turgunbaev, Mustafa.

- Watts RA, Lane S, Scott DG. What is known about the epidemiology of the vasculitides? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:191– 207.

- Ntatsaki E, Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of ANCA-associated Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2010;36:447– 61.

- Mahr A, Guillevin L, Poissonnet M, Aymé S. Prevalences of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg- Strauss syndrome in a French urban multiethnic population in 2000: a capture– recapture estimate. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:92– 9.

- Walton EW. Giant- cell granuloma of the respiratory tract (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Br Med J 1958;2:265– 70.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck- Ytter Y, Alonso- Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924– 6.

- Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck- Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:719– 25.

- Alexander PE, Gionfriddo MR, Li SA, Bero L, Stoltzfus RJ, Neumann I, et al. A number of factors explain why WHO guideline developers make strong recommendations inconsistent with GRADE guidance. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;70:111– 22.

- Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso- Coello P, et al. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach [review]. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;72:45– 55.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated N Engl J Med 2010;363:221– 32.

- De Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DR, Suarez LF, Gregorini G, Gross WL, et al. Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody—associated vas- culitis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:670– 80.

- De Groot K, Rasmussen N, Bacon PA, Tervaert JW, Feighery C, Gregorini G, et al. Randomized trial of cyclophosphamide versus methotrexate for induction of remission in early systemic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody– associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2461– 9.

- Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, Luqmani R, Morgan MD, Peh CA, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal N Engl J Med 2010;363:211– 20.

- Jayne DR, Gaskin G, Rasmussen N, Abramowicz D, Ferrario F, Guillevin L, et al. Randomized trial of plasma exchange or high- dosage methylprednisolone as adjunctive therapy for severe renal vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2180– 8.

- Walsh M, Casian A, Flossmann O, Westman K, Höglund P, Pusey C, et al. Long- term follow- up of patients with severe ANCA- associated vasculitis comparing plasma exchange to intravenous methylprednisolone treatment is unclear. Kidney Int 2013;84:397– 402.

- Walsh M, Merkel PA, Peh CA, Szpirt WM, Puéchal X, Fujimoto S, et al. Plasma exchange and glucocorticoids in severe ANCA- associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2020;382:622– 31.

- Chanouzas D, McGregor JA, Nightingale P, Salama AD, Szpirt WM, Basu N, et al. Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone for induction of remission in severe ANCA associated vasculitis: a multi-center retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2019;20:58.

- De Groot K, Reinhold- Keller E, Tatsis E, Paulsen J, Heller M, Nölle B, et al. Therapy for the maintenance of remission in sixty- five patients with generalized Wegener’s granulomatosis: methotrexate versus trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:2052– 61.

- Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Karras A, Khouatra C, Aumaître O, Cohen P, et al. Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance in ANCA- associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1771– 80.

- Pagnoux C, Mahr A, Hamidou MA, Boffa JJ, Ruivard M, Ducroix JP, et al. Azathioprine or methotrexate maintenance for ANCA- associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2790– 803.

- Smith R, Jayne D, Merkel PA. A randomized, controlled trial of rituximab versus azathioprine after induction of remission with rituximab for patients with ANCA- associated vasculitis and relapsing disease [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71 Suppl 10.

URL: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/a-randomized-controlled-trial-of-rituximab-versus-azathioprine-after-induction-of-remission-with-rituximab-for-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis-and-relapsing-disease/ - Smith RM, Jones RB, Guerry MJ, Laurino S, Catapano F, Chaudhry A, et al. Rituximab for remission maintenance in relapsing antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody– associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:3760– 9.

- Charles P, Terrier B, Perrodeau E, Cohen P, Faguer S, Huart A, et al. Comparison of individually tailored versus fixed-schedule rituximab regimen to maintain ANCA-associated vasculitis remission: results of a multicentre, randomised controlled, phase III trial (MAINRITSAN2). Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1143– 9.

- Hiemstra TF, Walsh M, Mahr A, Savage CO, de Groot K, Harper L, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil vs azathioprine for remission maintenance in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody– associated vasculitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:2381– 8.

- Metzler C, Miehle N, Manger K, Iking-Konert C, de Groot K, Hellmich B, et al. Elevated relapse rate under oral methotrexate versus leflunomide for maintenance of remission in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1087– 91.

- Stegeman CA, Tervaert JW, de Jong PE, Kallenberg CG. Trimethoprim– sulfamethoxazole (co- trimoxazole) for the prevention of relapses of Wegener’s granulomatosis. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:16– 20.

- Kado R, Sanders G, McCune WJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia after rituximab therapy [review]. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2017;29:228– 33.

- Karras A, Pagnoux C, Haubitz M, de Groot K, Puechal X, Tervaert JW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of prolonged treatment in the remission phase of ANCA- associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1662– 8.

- Harper L, Morgan MD, Walsh M, Hoglund P, Westman K, Flossmann O, et al. Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in ANCA- associated vasculitis: long- term follow- up. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:955– 60.

- Crickx E, Machelart I, Lazaro E, Kahn JE, Cohen- Aubart F, Martin T, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin as an immunomodulating agent in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitides: a French nationwide study of ninety- two patients. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:702– 12.

- Sachse F, Stoll W. Nasal surgery in patients with systemic disorders. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;9:Doc02.

- Congdon D, Sherris DA, Specks U, McDonald T. Long- term follow- up of repair of external nasal deformities in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope 2002;112:731– 7.

- Girard C, Charles P, Terrier B, Bussonne G, Cohen P, Pagnoux C, et al. Tracheobronchial stenoses in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): a report on 26 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1088.

- Terrier B, Dechartres A, Girard C, Jouneau S, Kahn JE, Dhote R, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis: endoscopic management of tracheobronchial stenosis: results from a multicentre experience. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:1852– 7.

- Martinez Del Pero M, Jayne D, Chaudhry A, Sivasothy P, Jani P. Long- term outcome of airway stenosis in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis): an observational study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:1038– 44.

- Joshi L, Tanna A, McAdoo SP, Medjeral-Thomas N, Taylor SR, Sandhu G, et al. Long- term outcomes of rituximab therapy in ocular granulomatosis with polyangiitis: impact on localized and nonlocalized disease. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1262– 8.

- Durel CA, Hot A, Trefond L, Aumaitre O, Pugnet G, Samson M, et al. Orbital mass in ANCA- associated vasculitides: data on clinical, biological, radiological and histological presentation, therapeutic management, and outcome from 59 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:1565– 73.

- Tomasson G, Grayson PC, Mahr AD, LaValley M, Merkel PA. Value of ANCA measurements during remission to predict a relapse of ANCA- associated vasculitis: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:100– 9.

- Vernovsky I, Dellaripa PF. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing immunosuppressive therapy: prevalence and associated features. J Clin Rheumatol 2000;6:94– 101.

- Sagmeister MS, Grigorescu M, Schönermarck U. Kidney transplantation in ANCA- associated vasculitis. J Nephrol 2019;32:919– 26.

- Geetha D, Eirin A, True K, Irazabal MV, Specks U, Seo P, et al. Renal transplantation in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody- associated vasculitis: a multicenter experience. Transplantation 2011;91:1370– 5.

- Stassen PM, Derks RP, Kallenberg CG, Stegeman CA. Venous thromboembolism in ANCA- associated vasculitis: incidence and risk factors. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:530– 4.

- Merkel PA, Lo GH, Holbrook JT, Tibbs AK, Allen NB, Davis JC Jr, et al. High incidence of venous thrombotic events among patients with Wegener granulomatosis: the Wegener’s Clinical Occurrence of Thrombosis (WeCLOT) Study. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:620– 6.

- Gayraud M, Guillevin L, le Toumelin P, Cohen P, Lhote F, Casassus P, et al. Long-term followup of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg- Strauss syndrome: analysis of four prospective trials including 278 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:666– 75.

- Mohammad AJ, Hot A, Arndt F, Moosig F, Guerry MJ, Amudala N, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg– Strauss). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:396– 401.

- Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, Khoury P, Klion A, Langford CA, et al. Mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1921– 32.

- Puéchal X, Pagnoux C, Baron G, Quémeneur T, Néel A, Agard C, et al. Adding azathioprine to remission- induction glucocorticoids for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss), microscopic polyangiitis, or polyarteritis nodosa without poor prognosis factors: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:2175– 86.

- Durel CA, Berthiller J, Caboni S, Jayne D, Ninet J, Hot A. Long-term followup of a multicenter cohort of 101 patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:374– 87.

- Comarmond C, Pagnoux C, Khellaf M, Cordier JF, Hamidou M, Viallard JF, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg- Strauss): clinical characteristics and long- term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:270– 81.

- Maritati F, Alberici F, Oliva E, Urban ML, Palmisano A, Santarsia F, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclophosphamide for remission maintenance in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a randomised trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185880.

- Teixeira V, Mohammad AJ, Jones RB, Smith R, Jayne D. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in the treatment of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. RMD Open 2019;5:e000905.

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1198– 207.

- Hauser T, Mahr A, Metzler C, Coste J, Sommerstein R, Gross WL, et al. The leucotriene receptor antagonist montelukast and the risk of Churg-Strauss syndrome: a case– crossover study. Thorax 2008;63:677– 82.

- Guillevin L, Gayraud M, Cohen P, Jarrousse B, Lortholary O, Thibult N, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg- Strauss syndrome: a prospective study in 342 patients [review]. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:17– 28.

- Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Seror R, Mahr A, Mouthon L, Le Toumelin P, et al, for the French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG). The Five- Factor Score revisited: assessment of prognoses of systemic necrotizing vasculitides based on the French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG) cohort. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:19– 27.

- Jayne DR, Merkel PA, Schall TJ, Bekker P, ADVOCATE Study Group. Avacopan for the treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:599–609.

Results

For the evidence report for GPA and MPA, the Literature Review team reviewed 729 articles to address 47 PICO questions. For the evidence report for EGPA, 190 articles were reviewed to address 34 PICO questions.

Recommendations and Ungraded Positions for GPA and MPA

Tables and Figures for GPA and MPA

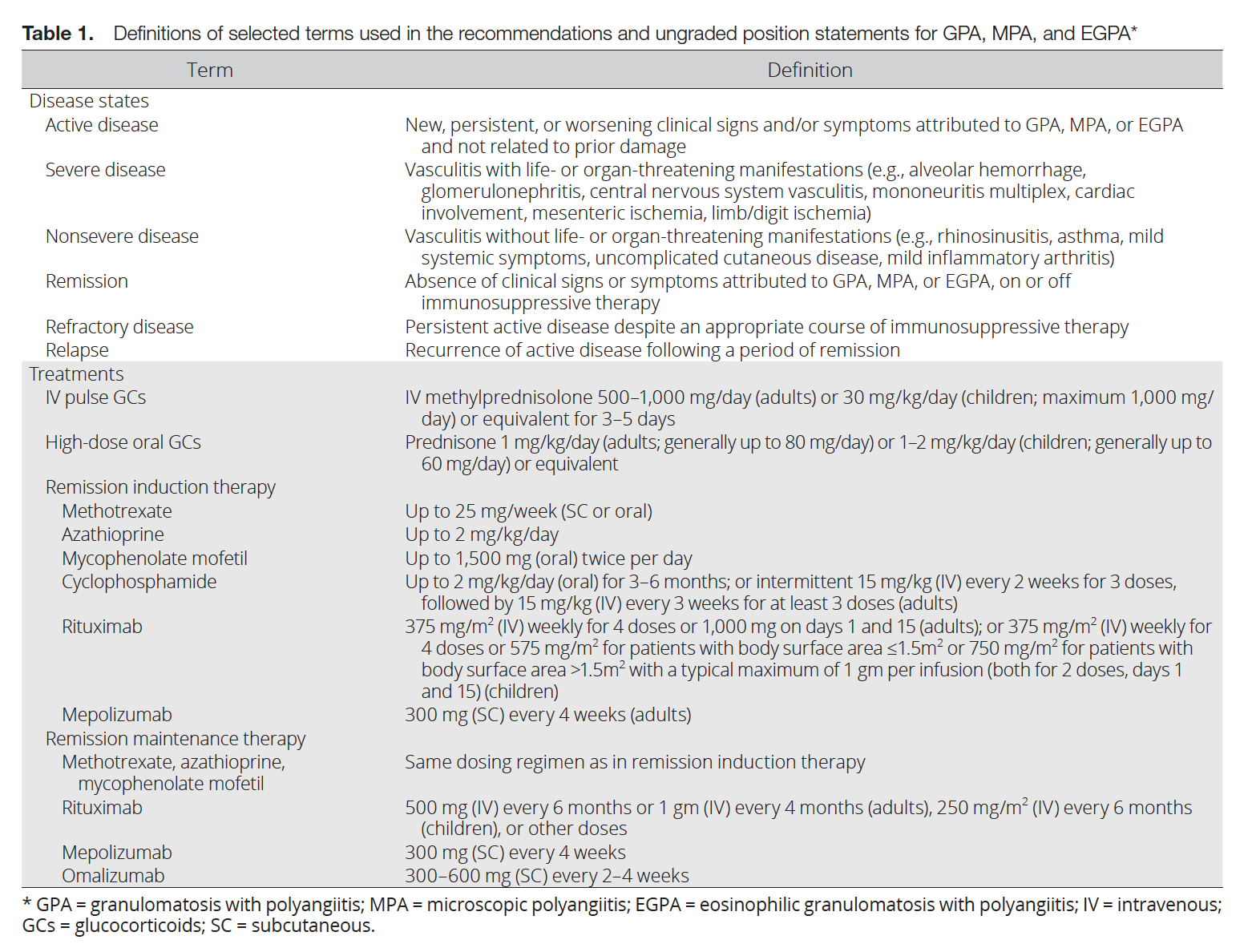

Table 1 presents the definitions of selected terms used in the recommendations and ungraded position statements, including the definition of severe and non-severe disease and the dosing regimens of medications used for remission induction and maintenance. Table 2 presents the recommendations and ungraded position statements with their supporting PICO questions and levels of evidence. Figure 1 presents key recommendations for the treatment of GPA and MPA.

Recommendations and ungraded positions for GPA and MPA

GPA and MPA are recognized as different diseases for which disease-specific management approaches exist. However, many recommendations and ungraded position statements consider GPA and MPA together, because pivotal trials have enrolled both groups and presented results for these diseases together. Therefore, we present recommendations and ungraded position statements applicable to both GPA and MPA as well as recommendations and ungraded position statements only applicable to GPA. All recommendations for GPA/MPA are conditional, due in part to a lack of multiple randomized controlled trials supporting the recommendations. The complete list of studies reviewed to form the recommendations is provided in the evidence report (Supplementary Appendix 2, http://onlin elibrary.wiley.com/doi/10. 1002/art.41773/ abstract). Given that these diseases affect multiple organ systems, collaboration between rheumatologists, nephrologists, pulmonologists, and otolaryngologists can enhance the care of patients with GPA and MPA.

Remission induction for active, severe disease for GPA and MPA

Recommendation: For patients with active, severe GPA/MPA, we conditionally recommend treatment with rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission induction.

Both rituximab and cyclophosphamide, in combination with glucocorticoids, have been used for remission induction in GPA and MPA. Rituximab has been shown to provide similar benefits to cyclophosphamide for remission induction in a randomized controlled trial (9). Although the currently used cumulative doses of cyclophosphamide are lower than previous regimens and result in less toxicity per treatment course, rituximab is still preferred, since rituximab is considered less toxic than cyclophosphamide. A single course of cyclophosphamide can carry substantial risks such as neutropenia, bladder injury, and the small but present potential for infertility which can be devastating to a young patient. Risks of malignancy and infertility increase when repeated courses of cyclophosphamide are used. Rituximab was also preferred by the Patient Panel, as a generally better-tolerated treatment. Retrospective studies suggest that the 2 remission induction regimens for rituximab used in adults (375 mg/m2 every week for 4 weeks [US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved dosing schedule] and 1,000 mg on days 1 and 15) are equally efficacious. The choice between these regimens should be guided by the patient’s preferences and values.

Cyclophosphamide (dosing provided in Table 1) may be used when rituximab needs to be avoided or when patients have active disease despite receiving rituximab treatment. It remains controversial whether cyclophosphamide should be preferred for certain types of severe disease, such as acute renal failure (e.g., serum creatinine >4.0 mg/dl). Either intravenous (IV) pulse or daily oral cyclophosphamide can be used (10,11). For adults, the decision between these 2 options should be based on patient and physician preferences. In children, IV cyclophosphamide may be preferred to facilitate compliance and limit toxicity. Data regarding the efficacy of combined cyclophosphamide and rituximab therapy for remission induction remain limited (12), and potential toxicity of this combination remains a concern. The combination of rituximab with cyclophosphamide is not widely used in the US, and its efficacy compared to rituximab or cyclophosphamide monotherapy is not established. This combination remains under study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03942887) at this time.

Recommendation: In patients with GPA/MPA with active glomerulonephritis, we conditionally recommend against the routine addition of plasma exchange to remission induction therapy.

Plasma exchange should not be initiated in all patients with active glomerulonephritis but can be considered for patients at higher risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who accept a potential increased risk of infection.

This recommendation is supported by data from the 2 largest trials of plasma exchange for the treatment of glomerulonephritis in AAV. The first trial, which required a serum creatinine level of ≥5.8 mg/dl for entry, showed that plasma exchange decreased the risk of ESRD but did not decrease mortality (13,14). In a more recent randomized trial of plasma exchange in AAV, the addition of plasma exchange to conventional remission induction therapy did not improve the composite outcome of ESRD or death; a decrease in the risk of ESRD was observed, but the result was not statistically significant (hazard ratio 0.81 [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.57–1.13]) (15).

However, combined data from these 2 trials show that there is probably a decreased risk of ESRD in patients with glomerulonephritis who received plasma exchange, compared to those who did not (hazard ratio 0.72 [95% CI 0.53–0.98]; moderate certainty) (Supplementary Appendix 2, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41773/ abstract). The benefit was most pronounced in patients with the highest risk of ESRD (118 fewer cases of ESRD per 1,000 cases of active glomerulonephritis [95% CI between 217 and 7 fewer cases]), although no difference in mortality was demonstrated (risk ratio 1.15 [95% CI 0.78–1.70]; moderate certainty). In 4 trials of plasma exchange in AAV, a higher risk of severe infection was observed with plasma exchange (risk ratio 1.19 [95% CI 0.99–1.42]; moderate certainty).

These findings suggest that for patients with a low risk of progression to ESRD, the risk of plasma exchange may outweigh the benefit; however, in patients with a higher risk of progression to ESRD, the decrease in risk could outweigh the increased risk of serious infection with plasma exchange. Therefore, the Voting Panel does not recommend plasma exchange for all patients with active glomerulonephritis but favors consideration of the treatment for patients at a higher risk of progression to ESRD. Factors that could influence whether plasma exchange is initiated include the patient’s kidney function upon presentation, rate of loss of kidney function, response to remission induction therapies, and the patient’s ability to tolerate serious infections.

Plasma exchange remains advisable in patients with GPA or MPA who also have anti-glomerular basement membrane disease.

Recommendation: In patients with active, severe GPA/MPA with alveolar hemorrhage, we conditionally recommend against adding plasma exchange to remission induction therapies.

Two trials evaluated the use of plasma exchange in patients presenting with alveolar hemorrhage, and no differences in mortality or remission rates were observed. Thus, plasma exchange does not have an established benefit for patients with alveolar hemorrhage and is associated with an increased risk of serious infection (see above recommendation). Plasma exchange may be considered for certain patients with active glomerulonephritis or those who are critically ill and whose disease is not responding to recommended remission induction therapies (i.e., plasma exchange as “salvage” or “rescue” therapy).

Plasma exchange remains advisable in patients with GPA or MPA who also have anti–glomerular basement membrane disease.

Ungraded position statement: For patients with active, severe GPA/MPA, either IV pulse glucocorticoids or high-dose oral glucocorticoids may be prescribed as part of initial therapy.

There are no trials comparing the efficacy of IV pulse glucocorticoids to high-dose oral glucocorticoids. Higher doses of glucocorticoids (such as pulse glucocorticoids) are generally administered to patients with organ-or life-threatening disease manifestations but may be associated with an increased risk of infection (16).

Recommendation: For patients with active, severe GPA/MPA, we conditionally recommend a reduced-dose glucocorticoid regimen over a standard-dose glucocorticoid regimen for remission induction.

A recent study demonstrated that a reduced-dose glucocorticoid regimen provided a similar benefit compared to a standard-dose regimen for the composite outcome of ESRD or death, and was associated with a decreased risk of infection (15). Due to the known toxicities associated with long-term glucocorticoid use, minimizing glucocorticoid exposure is critical to improving outcomes. Glucocorticoid dosing may be individualized for each patient. Of note, the reduced-dose regimen started with pulse methylprednisolone (3 daily pulses for maximum total dose of 3 gm) and 1 week of high-dose oral glucocorticoids. The dosing regimens used in this study are described in Supplementary Appendix 3 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41773/ abstract).

Remission induction for active nonsevere disease for GPA and MPA

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere GPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with methotrexate over cyclophosphamide or rituximab.

Nonsevere GPA is defined as GPA without life- or organ threatening manifestations (Table 1). Methotrexate, rituximab, and cyclophosphamide are effective at inducing remission in this patient group (11). However, like severe GPA, nonsevere GPA can be a chronic disease that requires multiple courses of therapy. Thus, the Voting Panel favored using therapies with potentially less toxicity before utilizing therapies with potentially more toxicity. Therefore, methotrexate is preferred due to the greater toxicity of cyclophosphamide. Methotrexate is currently recommended over rituximab because of the larger body of evidence and clinical experience with methotrexate treatment for this patient group; clinical trials are needed to compare their efficacy. Rituximab may be preferred in specific clinical situations, including for patients with hepatic or renal dysfunction, recurrent relapses while receiving methotrexate, or concerns regarding compliance.

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere GPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with methotrexate and glucocorticoids over glucocorticoids alone.

Methotrexate with glucocorticoids is recommended to minimize glucocorticoid exposure and toxicity. Overall, there are few clinical situations in which treatment with glucocorticoid monotherapy may be considered (e.g., arthralgias or inability to tolerate other remission maintenance therapies), and close monitoring is needed if this treatment strategy is used.

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere GPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with methotrexate and glucocorticoids over azathioprine and glucocorticoids or mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticoids.

The use of methotrexate for remission induction in this patient group is supported by more available data than other treatments (11), but azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil can be considered. Comparative effectiveness trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil for remission induction in active, nonsevere GPA. Clinical factors may influence the medication selected. For example, methotrexate should be used with caution or avoided in patients with moderate-to-severe renal insufficiency. Azathioprine is the preferred agent for pregnant patients or in patients who cannot tolerate methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil, while methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil is indicated in patients with total thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficiency or high-risk TPMT and/or NUDT15 genotypes.

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere GPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with methotrexate and glucocorticoids over trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and glucocorticoids.

Methotrexate is considered more effective than trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for remission induction, based on previous findings (17). Low-dose trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole may be administered concurrently with immunosuppressive agents to prevent Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (see GPA/MPA recommendation on this topic).

Remission maintenance for GPA and MPA

Recommendation: For patients with severe GPA/MPA whose disease has entered remission after treatment with cyclophosphamide or rituximab, we conditionally recommend treatment with rituximab over methotrexate or azathioprine for remission maintenance.

Rituximab is associated with a lower relapse rate than azathioprine when used for remission maintenance after remission induction with cyclophosphamide (18). Methotrexate and azathioprine have comparable efficacy rates for remission maintenance (19). Therefore, rituximab is favored over methotrexate or azathioprine. However, more long-term safety data are available for methotrexate and azathioprine, and cost and other factors may limit rituximab use.

Different doses of rituximab have been used for remission maintenance, including IV 500 mg every 6 months (18) (FDA-approved), IV 1,000 mg every 4 months (20), and IV 1,000 mg every 6 months (21). No comparative trials have been conducted. Thus, the optimal dose of rituximab for remission maintenance remains uncertain.

If methotrexate or azathioprine treatment is being considered for remission maintenance, the patient’s clinical situation, preferences, and values should guide selection between them, given their comparable efficacy.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA who are receiving rituximab for remission maintenance, we conditionally recommend scheduled re-dosing over using ANCA titers or CD19+ B cell counts to guide re-dosing.

In one randomized trial, patients who received rituximab for remission maintenance based on changes in CD19+ B cell counts and/or ANCA titers had similar rates of relapse as those receiving rituximab as a scheduled dose. However, this study was limited by the small sample size, and there were wide CIs for the effect size (22). This recommendation is based in part on the experience and expertise of the Voting Panel, which recognized that flares can occur when patients experience CD19+ B cell depletion and/or when test results for ANCA are negative. Thus, CD19+ B cell counts or ANCA titers may not accurately indicate the potential for a patient’s disease to flare.

Recommendation: For patients with severe GPA/MPA whose disease has entered remission after treatment with cyclophosphamide or rituximab, we conditionally recommend treatment with methotrexate or azathioprine over mycophenolate mofetil for remission maintenance.

Methotrexate and azathioprine are equally efficacious for remission maintenance (19). Azathioprine is favored over mycophenolate mofetil because the relapse rate with mycophenolate mofetil was higher than with azathioprine when studied for remission maintenance (23). Mycophenolate mofetil may still be considered for those unable to tolerate or with contraindications to methotrexate, azathioprine, or rituximab.

Recommendation: For patients with severe GPA/MPA whose disease has entered remission after treatment with cyclophosphamide or rituximab, we conditionally recommend treatment with methotrexate or azathioprine over leflunomide for remission maintenance.

Methotrexate or azathioprine treatment is recommended over leflunomide due to the data supporting and clinical experience using methotrexate and azathioprine for remission maintenance. The data and clinical experience with leflunomide are more limited. In one clinical trial comparing leflunomide to methotrexate treatment, leflunomide treatment demonstrated a decreased rate of relapse but a higher rate of drug withdrawal (24). The trial used a leflunomide dose of 30 mg/day, which may have contributed to toxicity.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA whose disease has entered remission, we conditionally recommend treatment with methotrexate or azathioprine over trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for remission maintenance.

The Voting Panel strongly favored the use of methotrexate or azathioprine over trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, but this recommendation is conditional due to the lack of sufficient high-quality evidence comparing the 2 treatments.

Recommendation: In patients with GPA whose disease has entered remission, we conditionally recommend against adding trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole to other therapies (e.g., rituximab, azathioprine, methotrexate, etc.) for the purpose of remission maintenance.

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole may have benefit for patients with sinonasal involvement (25), but its use potentially increases toxicity (e.g., severe hypersensitivity reactions) and medication burden. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole may still be indicated for prophylaxis against P jirovecii pneumonia (see GPA/MPA recommendation on this topic). There is a potential drug interaction between methotrexate and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole when trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is dosed at 800 mg/160 mg twice a day. The trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole dose used for Pneumocystis prophylaxis is generally tolerated, but its use should be monitored when used in conjunction with methotrexate.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA receiving remission maintenance therapy with rituximab who have hypogammaglobulinemia (e.g., IgG <3 gm/liter) and recurrent severe infections, we conditionally recommend immunoglobulin supplementation.

Immunoglobulin supplementation at replacement doses (e.g., 400–800 mg/kg/month) should be considered if a patient has hypogammaglobulinemia and is experiencing recurrent infections. Immunoglobulin supplementation can also be considered for patients with hypogammaglobulinemia without recurrent infections but with impaired vaccine responses (26). These considerations should be made in collaboration with an allergist/immunologist.

Ungraded position statement: The duration of nonglucocorticoid remission maintenance therapy in GPA/MPA should be guided by the patient’s clinical condition, preferences, and values.

The optimal duration of remission maintenance therapy is not well established. Although clinical trials have typically administered remission maintenance therapy for ≥18 months, patients may benefit from continuing remission maintenance therapy for a longer duration (27). The Patient Panel favored remission maintenance therapy for ≥18 months and potentially longer depending on patient-specific factors. Factors to be considered include previous relapse history, extent of organ involvement, and disease characteristics such as ANCA status (with PR3-ANCA– positive patients more likely to experience disease relapse [28]).

Ungraded position statement: The duration of glucocorticoid therapy for GPA/MPA should be guided by the patient’s clinical condition, preferences, and values.

The optimal duration of glucocorticoid therapy for GPA/MPA is not well established. The immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids contributing to disease control should be balanced with the toxicities associated with its use. Overall, patients expressed a desire to minimize the glucocorticoid dose as much as possible but recognized that some patients may require low-dose glucocorticoids long-term to maintain disease quiescence. Screening for toxicities of glucocorticoid use (e.g., bone mineral density testing for osteoporosis) should be conducted.

Treatment of disease relapse for GPA and MPA

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA who have experienced relapse with severe disease manifestations and are not receiving rituximab for remission maintenance, we conditionally recommend treatment with rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission re-induction.

Rituximab is more effective than oral cyclophosphamide for re-induction of remission among patients who previously received cyclophosphamide and then experienced relapse, based on subgroup analysis of a randomized controlled trial (9). In addition, the cumulative toxicity of cyclophosphamide raises concerns over repeated use of this agent.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA who experienced relapse with severe disease manifestations while receiving rituximab for remission maintenance, we conditionally recommend switching from rituximab to cyclophosphamide over receiving additional rituximab for remission re-induction.

Multiple factors can influence whether rituximab or cyclophosphamide treatment (IV or oral) is used, such as time since last rituximab infusion and cumulative cyclophosphamide dose. Cyclophosphamide is recommended if the patient recently received rituximab, while a remission induction dose of rituximab may be effective if an extended period has passed since the last rituximab infusion. As is standard for remission induction, these agents should be used in conjunction with glucocorticoids.

Treatment of refractory disease for GPA and MPA

Recommendation: For patients with severe GPA/MPA that is refractory to treatment with rituximab or cyclophosphamide for remission induction, we conditionally recommend switching treatment to the other therapy over combining the 2 therapies.

Disease refractory to remission induction therapy is rare, and there are limited data to guide treatment recommendations. Practitioners should evaluate whether other conditions such as infection could be mimicking vasculitis. However, if a patient’s disease is refractory to one remission induction therapy, it is important to change the remission induction strategy. We recommend switching to the other remission induction agent prior to using combination therapy.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA that is refractory to remission induction therapy, we conditionally recommend adding IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) to current therapy.

IVIG should not be used routinely to treat GPA/MPA but can be considered at certain treatment doses (e.g., 2 gm/kg) as adjunctive therapy for short-term control, while waiting for remission induction therapy (i.e., rituximab or cyclophosphamide) to become effective (see above recommendation) (29).

Treatment of sinonasal, airway, and mass lesions for GPA and MPA

Ungraded position statement: For patients with sinonasal involvement in GPA, nasal rinses and topical nasal therapies (antibiotics, lubricants, and glucocorticoids) may be beneficial.

We suggest collaborating with an otolaryngologist with expertise in treating GPA to determine whether these interventions should be used.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA in remission who have nasal septal defects and/or nasal bridge collapse, we conditionally recommend reconstructive surgery, if desired by the patient.

To optimize surgical outcomes, reconstructive surgery should be performed, after a period of sustained remission, by an otolaryngologist with expertise in treating GPA (30,31).

Recommendation: For patients with GPA and actively inflamed subglottic and/or endobronchial tissue with stenosis, we conditionally recommend treating with immunosuppressive therapy over surgical dilation with intralesional glucocorticoid injection alone.

Subglottic or endobronchial stenoses should be managed by an otolaryngologist or pulmonologist, respectively, with expertise in management of these lesions. Immunosuppressive therapy is recommended for initial treatment of active inflammatory stenoses and usually comprises glucocorticoids and other agents (32); the degree of immunosuppressive therapy utilized may be based on the severity of other disease manifestations. Surgical dilation with intralesional glucocorticoid injection may be more appropriate for stenoses that are longstanding, fibrotic, or unresponsive to immunosuppression

(32–34). Surgical dilation with intralesional glucocorticoid injection concurrent with medical treatment may also be considered as initial therapy for stenoses that require immediate intervention (e.g., critical narrowing).

Recommendation: For patients with GPA and mass lesions (e.g., orbital pseudotumor or masses of the parotid glands, brain, or lungs), we conditionally recommend treatment with immunosuppressive therapy over surgical removal of the mass lesion with immunosuppressive therapy.

Immunosuppressive therapy (with remission induction followed by remission maintenance) is almost always the initial treatment of choice for mass lesions (35,36). While these lesions tend to respond primarily to glucocorticoids, other agents are also usually used in hopes of having a glucocorticoid-sparing effect. Debulking surgery may be considered if there is an urgent need for decompression, such as acute visual loss due to optic nerve compression, or other life-or organ-threatening compression.

Other considerations for GPA and MPA

Recommendation: In patients with GPA/MPA, we conditionally recommend against dosing immunosuppressive therapy based on ANCA titer results alone.

Increases in ANCA titers/levels are only modestly informative as an indicator of disease activity (37) and are not reliable predictors of disease flares for individual patients. Increasing immunosuppressive therapy based on changes in ANCA titers/levels alone can result in unnecessary immunosuppression resulting in adverse events. Persistence of ANCA positivity does not necessarily indicate that continued immunosuppressive therapy is required. Instead, treatment decisions should be based on a patient’s clinical symptoms in conjunction with diagnostic studies (e.g., laboratory, imaging, and biopsy findings).

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA who are receiving rituximab or cyclophosphamide, we conditionally recommend prophylaxis to prevent P jirovecii pneumonia.

Prophylaxis to prevent P jirovecii pneumonia is routinely used with cyclophosphamide treatment (38). The prescribing information for rituximab recommends prophylaxis for P jirovecii pneumonia for ≥6 months after the last rituximab dose for patients with GPA or MPA. While many on the Voting Panel felt strongly that patients with GPA/MPA receiving cyclophosphamide or rituximab should receive prophylaxis against P jirovecii pneumonia, this recommendation is conditional given the lack of moderate or high-quality evidence directly addressing this question and the potential toxicity of the medications used for prophylaxis. Prophylaxis against P jirovecii pneumonia should also be considered for patients receiving moderate-dose glucocorticoids (e.g., >20 mg/day) or higher in combination with methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil (38). Prophylaxis is less commonly used in younger children receiving rituximab but should be considered.

Recommendation: For patients with GPA/MPA inremission and stage 5 chronic kidney disease, we conditionally recommend evaluation for renal transplantation.

Outcomes of kidney transplantation in patients with AAV are similar to those in patients receiving transplants for other reasons, with disease relapses in the transplanted kidney being rare (39,40). GPA and MPA in remission should not be considered a contraindication to kidney transplantation, but these patients should be monitored for disease relapse after transplantation.

Recommendation: For patients with active GPA/MPA who are unable to receive other immunomodulatory therapy, we conditionally recommend administering IVIG.

IVIG should not be used routinely to treat GPA/MPA (see above recommendation). However, in the rare instances in which patients with active disease may not be able to receive conventional immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., sepsis or pregnancy), IVIG can be used as a short-term

intervention until conventional remission induction therapies can be used (29).

Ungraded position statement: The optimal duration of anticoagulation is unknown for patients with GPA/MPA who experience venous thrombotic events.

AAV is associated with an increased risk of venous thrombotic events, including both deep vein thromboses and pulmonary emboli (41,42). Venous thromboembolic events that occur in a patient with active disease and no other risk factors can be considered a provoked event with a transient risk factor (assuming subsequent disease control). Thus, short-term instead of lifelong anticoagulation may be considered.

Recommendations and Ungraded Positions for EGPA

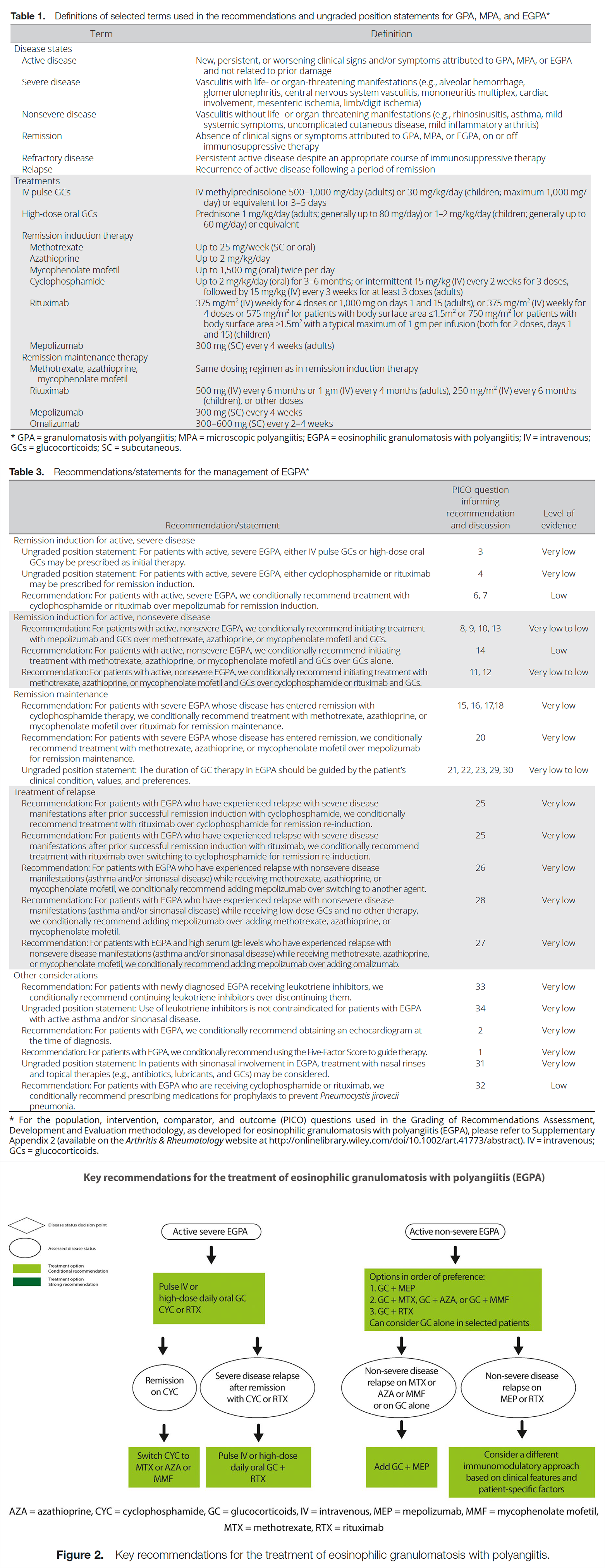

Table 1 presents the definitions of selected terms used in the recommendations and ungraded position statements, including the definition of severe and nonsevere disease and the dosing regimens of medications used for remission induction and maintenance. Table 3 presents the recommendations and ungraded position statements with their supporting PICO questions and levels of evidence. Figure 2 presents key recommendations for the treatment of EGPA.

Recommendations and Ungraded Positions for EGPA

EGPA is characterized by diverse features, including asthma, allergic rhinitis, peripheral and tissue eosinophilia, and vasculitis. As these clinical features can potentially have differing responses to treatment, the management approach is typically based on a patient’s disease features and severity. The recommendations presented here focus primarily on the use of immunosuppressive medications to treat the vasculitic manifestations of EGPA. However, asthma and allergic manifestations are a significant component of EGPA, and measures directed toward these, including inhaled therapies and allergen avoidance, play an important role in management. Collaboration between rheumatologists, asthma/allergy specialists, and specialists in other medical disciplines can enhance the care of patients with EGPA. In contrast to GPA/MPA, there have been very few randomized controlled trials conducted to date in EGPA. These recommendations and ungraded position statements therefore reflect reliance on lower-quality (i.e., indirect) evidence, including expert opinion.

Remission induction for active, severe disease for EGPA

Ungraded position statement: For patients with active, severe EGPA, either IV pulse glucocorticoids or high-dose oral glucocorticoids may be prescribed as initial therapy.

There are no data to support favoring either IV pulse or high-dose oral glucocorticoids over the other option in active, severe EGPA. Choosing an approach should be influenced by individual patient factors. In either instance, glucocorticoids should be combined with a nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressive agent such as cyclophosphamide or rituximab (see ungraded position statement below).

Ungraded position statement: For patients with active, severe EGPA, either cyclophosphamide or rituximab may be prescribed for remission induction.

Cyclophosphamide has been more commonly used for remission induction in patients with active, severe EGPA, given the experience with cyclophosphamide in other forms of vasculitis (43). Increasing experience with rituximab in GPA/MPA has also led to more patients with EGPA being treated with rituximab, and case series suggest that rituximab may also have efficacy for active, severe disease (44). Given that the comparative effectiveness of cyclophosphamide and rituximab for EGPA is unknown, the Voting Panel felt that both cyclophosphamide and rituximab could be considered for remission induction in active, severe EGPA. Cyclophosphamide would be preferred for patients with active cardiac involvement given the increased experience with cyclophosphamide, as cardiomyopathy has been found to be the main independent predictor of death in EGPA (25,26). Cyclophosphamide can also be considered for patients who are ANCA-negative and have severe neurologic or gastrointestinal manifestations. Rituximab may be considered for patients with positive ANCA results, active glomerulonephritis, prior cyclophosphamide treatment, or those at risk of gonadal toxicity from cyclophosphamide.

Recommendation: For patients with active, severe EGPA, we conditionally recommend treatment with cyclophosphamide or rituximab over mepolizumab for remission induction.

The efficacy of mepolizumab in severe EGPA has not been established, as patients with active, severe disease were excluded from the randomized trial (45). Rituximab or cyclophosphamide is recommended over mepolizumab in this setting.

Remission induction for active non-severe disease for EGPA

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere EGPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with mepolizumab and glucocorticoids over methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticoids.

A range of immunosuppressive agents may be considered in the treatment of active, nonsevere EGPA, all of which are used with glucocorticoids. The clinical profile of nonsevere EGPA includes predominantly asthma, sinus disease, and nonsevere vasculitis. While there is significant clinical experience with methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, there are limited data regarding their efficacy, and these treatments have not been assessed in randomized clinical trials. The GRADE methodology used in the guideline development process weights clinical trials more heavily than observational studies. Thus, mepolizumab is recommended as the first choice, because it has been found to be efficacious for nonsevere EGPA in a randomized trial (45). All patients in this trial had relapsing or refractory disease, with 55% receiving an additional nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressive agent at the time of enrollment. A large proportion of patients in this trial had asthmatic and eosinophilic features, for which mepolizumab has also been found to be effective in non-EGPA disease settings. Although patients with nonsevere vasculitic manifestations were represented in this trial, questions remain about the effectiveness of mepolizumab for all aspects of nonsevere vasculitis. Individual factors, including disease manifestations, may impact the decision to use mepolizumab, in which case methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil may be used instead. There are insufficient data to favor one of these medications (methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil) over the others; therefore, the choice should be influenced by individual patient factors.

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere EGPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticoids over glucocorticoids alone.

Patients should be treated with adjunctive methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil rather than glucocorticoids alone in order to minimize glucocorticoid toxicity. One randomized trial that combined patients with EGPA, MPA, and polyarteritis nodosa without poor prognosis factors showed that the addition of azathioprine did not provide benefit beyond glucocorticoids alone (46). Particularly for patients with asthma, this may impact the decision to use methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil concurrently with glucocorticoids and could lead to consideration of mepolizumab. Glucocorticoid monotherapy may be appropriate for mild asthma, allergic symptoms, use during pregnancy, or other individual patient situations.

Recommendation: For patients with active, nonsevere EGPA, we conditionally recommend initiating treatment with methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticoids over cyclophosphamide or rituximab and glucocorticoids.

While the comparative efficacy of methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab is not well established, the use of methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil is favored, based on more experience with these agents in EGPA compared to rituximab. However, rituximab may be considered if other agents are not effective in controlling active, nonsevere disease, or if the patient has nonsevere vasculitis (which in some series included mononeuritis multiplex) and is positive for ANCA. Cyclophosphamide should be avoided when treating active, nonsevere disease due to its toxicity and is the least preferred option in this setting.

Remission maintenance for EGPA

Recommendation: For patients with severe EGPA whose disease has entered remission with cyclophosphamide therapy, we conditionally recommend treatment with methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil over rituximab for remission maintenance.

Typically, a maintenance agent would be used after remission induction in severe EGPA to reduce toxicity and the risk of disease relapse (47), although monophasic disease can occur (48). Azathioprine has been commonly used in published EGPA series (46), but the lack of comparative evidence between methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil in EGPA precludes recommending one agent over another.

Use of methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil is recommended over rituximab, because there has been less experience with the use of rituximab for remission maintenance in EGPA. Rituximab could be considered if remission were induced with rituximab or if there are contraindications to other choices.

Recommendation: For patients with severe EGPA whose disease has entered remission, we conditionally recommend treatment with methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil over mepolizumab for remission maintenance.

While there are limited data informing the use of remission maintenance therapy in EGPA, remission induction therapies (e.g., cyclophosphamide) should not be indefinitely continued given the potential toxicity. Thus, methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil can be considered for remission maintenance based on experience in GPA/MPA, expert opinion, and results from small studies (49). The primary experience with mepolizumab is in refractory nonsevere disease, and thus it is difficult to extrapolate its efficacy as a remission maintenance agent for severe disease.

Ungraded position statement: The duration of glucocorticoid therapy in EGPA should be guided by the patient’s clinical condition, values, and preferences.

There is insufficient published evidence to support a specific duration of glucocorticoid treatment, and thus, the length of glucocorticoid therapy should be determined based on each patient’s clinical circumstances. Many patients with EGPA require some treatment with glucocorticoids, generally at a low dose, to maintain control of asthma and allergy symptoms.

The minimum effective dose should be prescribed to minimize glucocorticoid toxicity.

Treatment of disease relapse for EGPA

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA who have experienced relapse with severe disease manifestations after prior successful remission induction with cyclophosphamide, we conditionally recommend treatment with rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission re-induction.

Rituximab is favored based on the general desire to avoid re-treatment with cyclophosphamide if possible and on the findings of an observational study of rituximab in relapsing or refractory EGPA (50). Cyclophosphamide may be considered in instances of recurrent cardiac involvement, since cardiac involvement is an independent predictor of death and is associated with ANCA-negative disease, as discussed in the ungraded position statement about remission induction in active, severe disease.

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA who have experienced relapse with severe disease manifestations after prior successful remission induction with rituximab, we conditionally recommend treatment with rituximab over switching to cyclophosphamide for remission re-induction.

Re-induction of remission with rituximab is favored over cyclophosphamide treatment to minimize toxicity. However, the duration of remission prior to the onset of relapse should be examined. Cyclophosphamide should be considered if a severe relapse occurred quickly after rituximab treatment, or if cardiac involvement is present (see ungraded position statement and recommendation on this topic).

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA who have experienced relapse with nonsevere disease manifestations (asthma and/or sinonasal disease) while receiving methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil, we conditionally recommend adding mepolizumab over switching to another agent.

For patients with EGPA with active asthma, inhaled therapies should be maximized prior to increasing systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Although no direct comparative data are available, mepolizumab was found to be efficacious in a randomized trial in patients specifically described in this recommendation: those with relapsing nonsevere EGPA who are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (45). It has also been independently proven to be effective in eosinophilic asthma (51). Based on this evidence, mepolizumab is recommended to treat nonsevere relapsing disease in patients receiving methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil rather than switching to an alternative agent of that group.

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA who have experienced relapse with nonsevere disease manifestations (asthma and/or sinonasal disease) while receiving low-dose glucocorticoids and no other therapy, we conditionally recommend adding mepolizumab over adding methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil.

Similar to the discussion about the above recommendation, use of inhaled agents should be optimized in patients experiencing disease relapse with asthma and/or sinonasal disease. For patients with nonsevere relapsing EGPA who are receiving glucocorticoid monotherapy, starting mepolizumab would be preferred over adding methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil, given the treatment’s proven efficacy in this population in a randomized trial (45).

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA and high serum IgE levels who have experienced relapse with nonsevere disease manifestations (asthma and/or sinonasal disease) while receiving methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil, we conditionally recommend adding mepolizumab over adding omalizumab.

The published evidence on omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in EGPA has been limited. Therefore, even for a patient with high serum IgE levels, mepolizumab is the preferred choice based on evidence from the randomized controlled trial (45).

Recommendation: For patients with newly diagnosed EGPA receiving leukotriene inhibitors, we conditionally recommend continuing leukotriene inhibitors over discontinuing them.

Following the introduction of leukotriene inhibitors, concerns were raised about a link with the development of EGPA. In subsequent retrospective studies, it was not concluded that there is a causal relationship between leukotriene inhibitors and EGPA (52). Therefore, patients with newly diagnosed EGPA should have the option to continue a leukotriene inhibitor if it is beneficial in the management of their asthma or sinonasal disease.

Ungraded position statement: Use of leukotriene inhibitors is not contraindicated for patients with EGPA with active asthma and/or sinonasal disease.

Leukotriene inhibitors carry therapeutic indications for asthma and allergic rhinitis. As no clear causal association with EGPA has been demonstrated, a leukotriene inhibitor can be added to help manage asthma and sinonasal disease. However, leukotriene inhibitors are one of many options and are not the only choice in this setting. Leukotriene inhibitors should not be used to treat manifestations aside from asthma and sinonasal disease.

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA, we conditionally recommend obtaining an echocardiogram at the time of diagnosis.

Cardiac involvement is the major cause of disease-related mortality in EGPA (48). Echocardiography has minimal risk and can identify cardiac involvement, which, if present, can impact treatment decisions. Not identifying cardiac involvement could negatively impact patient outcomes. Thus, we recommend obtaining an echocardiogram for all patients with newly diagnosed EGPA, even in the absence of cardiac symptoms.

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA, we conditionally recommend using the Five-Factor Score to guide therapy.

The Five-Factor Score (FFS), first published in 1996 (53), was based on a cohort of 342 patients with either polyarteritis nodosa, as it was then defined, or EGPA. These 5 factors include proteinuria >1 gm/day, renal insufficiency with serum creatinine >1.58 mg/dl, gastrointestinal tract involvement, cardiomyopathy, and central nervous system involvement. The FFS is primarily a prognostic tool for which higher scores have been associated with a worse outcome (53). It has been used to guide treatment (43), but its applicability to newer therapies is unknown. The FFS was revisited in 2011 in a population of 1,108 patients with GPA, MPA, EGPA, or PAN (54). The 2011 version included ear, nose, and throat parameters and age >65 years. The 1996 FFS remains more commonly used and may be helpful in identifying organ-specific parameters associated with severe disease and in guiding treatment. Although the definitions of severe and nonsevere EGPA used in the present guideline were not based on the FFS, the tool was found to be useful to clinicians for making treatment decisions. The components of the FFS can serve as markers of severe disease that warrant more aggressive treatment.

Ungraded position statement: In patients with sinonasal involvement in EGPA, treatment with nasal rinses and topical therapies (e.g., antibiotics, lubricants, and glucocorticoids) may be considered.

Allergic rhinitis and sinonasal disease are frequent clinical features of EGPA. Although the efficacy of nasal rinses and topical therapies in EGPA is not well established, some patients may benefit. Where possible, consultation with an otolaryngologist with expertise in treating AAV should be obtained to guide the use and choice of these agents. These interventions can continue to be beneficial even when symptoms have improved or resolved.

Recommendation: For patients with EGPA who are receiving cyclophosphamide or rituximab, we conditionally recommend prescribing medications for prophylaxis to prevent P jirovecii pneumonia.

Prophylaxis to prevent P jirovecii pneumonia is discussed above in the GPA/MPA recommendations. The same considerations regarding prophylaxis to prevent this condition in patients with GPA/MPA apply to those with EGPA.