Blog

Samantha SainteMarie was in graduate school, working to get her master’s degree in mental health counseling, when it first happened. She was typing a research paper and noticed that her legs and feet had swollen. By the time the swelling went down, purpura–purple patches on her skin–were all over. “It looked like a port wine stain,” she recalled.

It took years–and many people misdiagnosing her or misbelieving her symptoms–before she was officially diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) vasculitis. She was in her mid-to-late 20s and was told to go on rituximab and methotrexate. It was 2005. “Being told you need infusions is scary,” Samantha said. “At the time, the doctors were still referring to them as chemotherapy meds. And everyone has an image of what chemotherapy patients look like.” Doctors didn’t refer her to support groups or resources. She didn’t have anyone to talk to who had been on this journey.

But what concerned her most was fertility: Would these drugs affect her desire to become a mother? “I remember my rheumatologist being really honest with me,” she said. “They said it could affect my fertility but, at that point, in 2005, they didn’t really know. There had been no research into GPA and pregnancy.”

Samantha and her husband were left to grapple with big “what-ifs.” What if the pregnancy is too taxing on my body? What if I can’t get pregnant? Once she started methotrexate and rituximab, her periods stopped. Would she even be able to carry a pregnancy to term? What if I’m halfway through the pregnancy, she wondered, and start to have renal involvement? What if the pregnancy gets to a point where it’s threatening my life? A lot of people, she realized, are privileged not to have to think about these “what-ifs.” But for her, these weren’t distant possibilities; they were real. They decided to go forward, anyway. “We just hoped for the best.”

Getting pregnant with vasculitis requires planning and coordination with an entire care team. Six months before even trying to get pregnant, Samantha was advised to stop her methotrexate medication. “Would this lead to a flare?” she worried. She had no choice but to try it, wait, and see.

Two months after she and her husband started trying, she was pregnant. When Samantha confirmed her positive pregnancy results, she was referred to a high-risk OB/GYN practice. At the time, she was living in Maine and there was only one high-risk OB/GYN practice in the state, about an hour away from where she was living.

She considered herself lucky. “Maine’s a really big state,” she explained. “There are people who live up north and it takes them the whole day to travel to this practice. I was seeing high-risk OB doctors every two weeks. There were tolls on the roads I had to pay.” Samantha was pointing to inequities in health care access. Becoming a mother with vasculitis presents many barriers; she felt fortunate, despite everything, to be able to face many of those obstacles with support and high-quality health care.

Many fears swirled around Samantha’s pregnancy, but it was a relatively healthy pregnancy. She didn’t experience any flares. The baby was developing well at each check-in. By 41 weeks pregnant, they insisted on inducing her.

Small blood clots and hemorrhaging during delivery didn’t stop her son from arriving in the world healthy.

But a month postpartum, her fortunes shifted. She had a flare. She remembers experiencing fullness and ringing in her ears–“like being on an airplane,” she said, “except it just didn’t stop.” A few months later, she started having excessive thirst and intense migraines, though she had never had a migraine before. “It was the most pain I ever had in my head, temple to temple.” She was sensitive to light and nauseous and had vision changes. Multiple trips to the ER left her without any answers.

She remembers her husband repeatedly driving her to the ER, their infant son with them because they were living far from family who could care for him. Her husband was a doctor and had taken her to his hospital; when they dismissed her, he was frustrated. These were his colleagues–and, still, no one was listening to his wife or his theories.

Her husband pushed for a lumbar puncture. The consulting neurologist finally agreed. It would take over a year for her to be diagnosed with a second form of vasculitis: central nervous system vasculitis (CNSV).

During this time, she struggled with new motherhood. She was put on hormone replacement therapy for her excessive thirst and urination. It got so bad that she would avoid grocery shopping. “There were times when I couldn’t find a bathroom in time,” she said. “It got very isolating because I didn’t want to leave the house.”

With these flares, Samantha felt like she couldn’t take care of her son. “For me, emotionally,” she said, “it was hard. It felt like one hit after another.”

What Samantha craved was a village of support. “Because I look okay,” she said, “people forget that this is a life-threatening disease. It’s easy for a lot of people in my life to lose that perspective.”

“My dad still doesn’t know the name of my disease. It feels hurtful. Why don’t you care enough to know?” To explain her illness to family, she often keeps it simple by just saying, “I’m on chemotherapy treatment.” Still, not everyone gets it. “I’ve had to miss family weddings in the past couple of years due to the pandemic.” She feels like some people try to guilt her into coming, anyway, saying, “We really want to see you.” They don’t understand that, as Samantha puts it, “this virus can take me out.”

There have been struggles in her family over vaccinations and COVID conspiracy theories. They’ve had to have difficult conversations with her mother-in-law about whether the grandkids can visit her if she’s not vaccinated. “We want to start seeing people again,” Samantha started crying. “But the anxiety of it; there’s a risk involved for me.”

Samantha and her husband recently had another child, a daughter. She didn’t want her son to grow up alone. “I kept thinking,” Samantha said, “when I eventually pass, it will just be my son. You don’t always appreciate siblings when you’re younger, but you appreciate them as you get older, especially when your parents are going through a lot of medical stuff.”

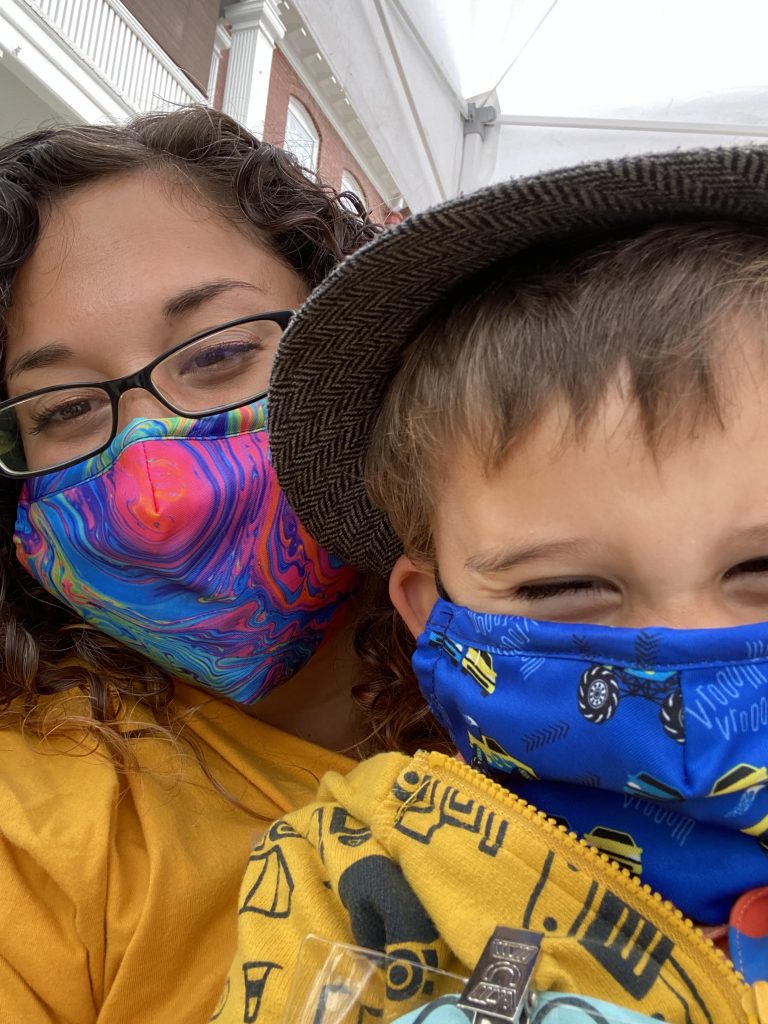

It took almost a year to coordinate her medication and plans for another pregnancy with all her providers. Her daughter is 1 now. With her second pregnancy, she participated in VPREG, the Vasculitis Pregnancy Registry, a patient-driven, global, online database that gathers the experiences of women with vasculitis during pregnancy. She participated to help other families in the future have the research and information she didn’t have during her first pregnancy.

Today, having been through it, she offers compassionate advice for other women with vasculitis who want to become moms. “It’s scary,” she admitted. “It’s hard. You don’t know what to expect. You’ll likely have to go off your meds. It’s important to make sure your whole care team is involved, that everyone is on the same page.” She also insists that you have the important conversations about potential obstacles now, before you’re pregnant. “Ask all the ‘what-ifs.’ What if you have a flare; what are the options? What if you don’t get pregnant? What are you willing to put your body through? How many miscarriages?” She went on, “You can’t do it alone. You need a support system.”

Samantha’s life is not what she expected when she was typing that paper in graduate school. She expected to lead a fulfilling career, but hasn’t been able to work since her first pregnancy. She’s not sure when her body and mind will be ready to go back.

Crying, she told me, “I just want to make it to my son’s high school graduation.”

“I think about end-of-life stuff,” she said. “My husband doesn’t like me to talk about it. But, for me, having this disease and the brain involvement, it’s made me think: What’s the legacy I want to leave behind?”

The answer she has discovered is community. She wants to continue to find ways to get involved with the spaces and people around her and to embrace her community with compassion. She volunteers and brings her kids with her. “I’m still trying to find what’s important to me and be active in that.”

Despite everything, Samantha is grateful. “I have two babies,” she said. “Both are healthy. I have the ability to be home with them, which is great. I don’t know many families that can afford one income. I know it’s a privilege. My life plan has definitely been impacted by this disease. But at least I’m still here. I’m still here with my kids.”