Blog

Art Diaz was living a full life in Southern California and rarely got sick. He was fit; a runner. Every few years, he’d force himself to see his primary care doctor, but the doctor would give him a clean bill of health and he’d go on his way for another few years. Art thought of himself as a healthy guy with a strong immune system.

Until he didn’t. In the spring of 2017, he started feeling arthritis-like pain. An avid runner, he wrote it off as an injury. Then came the shoulder pain. The last straw was when he started having trouble breathing. Finally, he went to the ER.

At first, the doctors in the ER thought he was having a heart attack. Instead, they diagnosed him with blood clots. “It was very scary,” Art said. “I thought I was the last person who should get blood clots. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke. I said to them, ‘There’s no way.’”

Eventually, the hospital sent him home and assigned him to a pulmonologist and a cardiologist. By this point, Art was really sick. His cardiologist, whose wife was a rheumatologist, had a hunch that it might be autoimmune. He suggested Art see her right away. Almost immediately, she diagnosed him with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Unfortunately, you don’t get diagnosed with vasculitis and then get

handed a guidebook or a mentor who can help you navigate the journey. Instead, Art’s rheumatologist put him on pre

dnisone and gave him a single sheet of paper with some basic information about the disease, but it was far from comprehensive.

As his wife drove them home from his appointment, Art began searching “vasculitis” on his phone. He was startled. He told his wife she had to pull over. “Oh, my gosh,” he said to her. “This is rare. Potentially fatal.” Their world came to a crashing halt.

Today, Art knows that a lot of the information he initially found online was outdated. But back then, it was terrifying. He decided not to google anything about the disease.

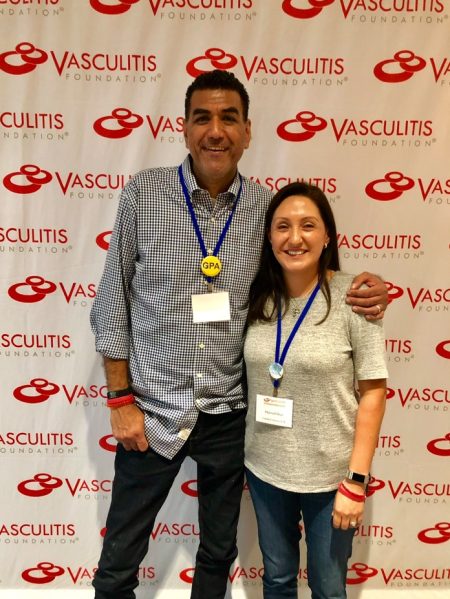

When he emerged from that informational blackout, he discovered the Vasculitis Foundation (VF). Art said, “There are many physical attributes to this disease, but above all, it’s mental. You feel alone, you feel isolated. You don’t know who to talk to. Fifty percent of people with a rare disease don’t have a foundation to support their disease. I feel lucky that we have the VF in our corner.”

With the VF on his side, he began to welcome back the light.

Art considers himself fortunate. His cardiologist happened to be married to a rheumatologist, which meant he got access to a specialist, a diagnosis, and treatment within three weeks after his hospital visit.

The more involved he got with the VF and the more connections he made with other people and family members impacted by vasculitis, the more he realized how rare his situation was. “Over and over, others told me their stories about the obstacles they faced to getting diagnosed or access to medication.” When they’d explain their symptoms to their physicians, the doctors would be stumped. They didn’t know how to treat them. In fact, Art sometimes found himself a curiosity to doctors. “There were a few times I went to the ER and a doctor would say to me, ‘I remember studying this, but I’ve never had a vasculitis patient.’” Some doctors would come up to him just to ask him questions since they hadn’t ever met someone living with the disease.

When Art was diagnosed, his treatment protocol included infusions of a drug called rituxan. Gratefully, his insurance covered all twelve treatments. But Art kept hearing from other people with vasculitis who told him their insurance didn’t cover their infusions. If they wanted the care they needed, it would be $15-20k per treatment, meaning they had two options: get the treatment their doctors strongly recommended and go into severe debt, or go without adequate care.

Art couldn’t put these stories out of his mind. He knew he had the power to speak up.

Today, Art shares his journey and raises vasculitis awareness on his social media account. But he’s careful: “By no means do I want people to feel sorry for me.”

Today, Art shares his journey and raises vasculitis awareness on his social media account. But he’s careful: “By no means do I want people to feel sorry for me.”

He continues to run races and often wears his Victory Over Vasculitis shirt, a VF program that highlights three pillars of wellness: mental health, physical health, and self-advocacy. Almost always, he’ll get a tap on the shoulder at a race, someone asking him what vasculitis is or if he knows someone who has it. “I do,” he says. “It’s me.”

Recently, he participated in an autoimmune congressional “fly-in,” where he met via Zoom with congressional staffers. “A lot of times, there’s oversight in funding for rare diseases. Legislators wonder if it’s worth investing in a disease when few people are impacted.” This is why Art believes it’s important to tell his story: for policymakers who control funding, sharing his experience puts a human face to vasculitis. In this way, people like him are no longer just a statistic.

What inspires Art the most is celebrating small victories alongside others living with the disease. At the VF, we call it our “victories over vasculitis.” Art described it: “People will tell me, I used to walk my dog or do puzzles, or I was in a book club. It’s just about going out the door and doing those, again.”

A story that sticks with him is a victory a woman shared a few years ago: “Today, I went to the grocery store,” she said. “I did all my shopping, put all my groceries away myself. I haven’t done that in two years.”

A story that sticks with him is a victory a woman shared a few years ago: “Today, I went to the grocery store,” she said. “I did all my shopping, put all my groceries away myself. I haven’t done that in two years.”

Art remembers those little victories. When he first got sick, he spent days on the couch or in bed. “I had to crawl from one to the other. I was scared. What was happening to me?” Five years later, he’s committed to letting others know that it gets better. “It took me a long time to get back to leading a normal life. There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about vasculitis, but, now, it doesn’t engulf my whole day.”

Art is finding light along the journey, and he’s doing everything he can to welcome others into that light, helping them trust in and find their own brightness.

Author: Ashley Asti